I was most excited to hear that Camping Con was going to be held at Great Smoky Mountains National Park, because GRSM had two Job Corps centers between 1965 and 1969. In fact, Oconaluftee Job Corps Center still operates today. I haven’t had a chance to look at either of these centers, so I saw Camping Con as an opportunity to learn more about them. I put in a proposal to Camping Con to lead a “War on Poverty Hike” and was selected. Since the conference would take place at Cades Cove Campground, I decided to do a tour of Tremont, which is now the Great Smoky Mountains Institute, an environmental education center, less than ten miles away. I reached out to GSMI staff and they were happy to meet with me. Staff took me on a tour of the facility in September.

Entrance to GSMI at Tremont showing bridge over Middle Prong of Little River.

Let me back up a moment to explain my interest in the Job Corps. The Job Corps was a War on Poverty program that was essentially a 1960s reboot of the Civilian Conservation Corps. It was set up a lot like the CCC, but there were two notable differences. First, the CCC was created as a response to an economic crisis, the Great Depression. The Job Corps was born during a moment of unprecedented American prosperity, which highlighted persistent pockets of poverty in places like Appalachia and inner cities. Second, the CCC was segregated, but the Job Corps was purposely integrated during an important phase of the Civil Rights Movement. The NPS was heavily involved in establishing the program and operated nine centers in eight national parks between 1965 and 1969, but it is a very little known chapter in the agency’s history. Since 2012, I’ve had the chance to research and write about the centers at Catoctin Mountain Park and Cumberland Gap National Historical Park. I’ve also surveyed Job Corps resources at Mammoth Cave National Park a few years ago. I’ve found that these centers had pretty significant impacts to national park landscapes and much evidence can still be found.

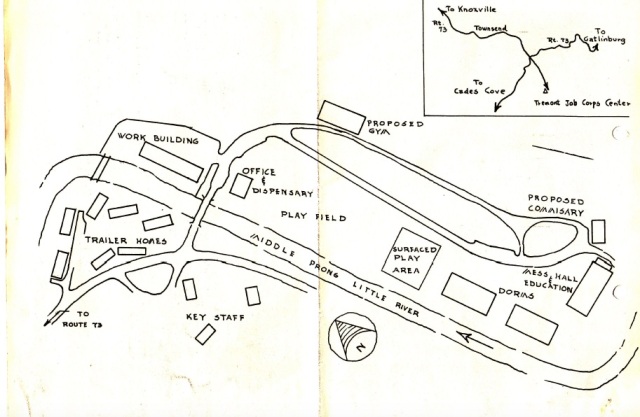

Great Smoky Mountains Institute is located on the former campus of the Tremont Job Corps Conservation Center (here’s a map of campus today). The campus itself is a layered landscape. In 1859, Will and Nancy Walker settled in the area. In 1924, the Little River Lumber Company logged the area. In 1925, Colonel W.E. Townsend donated eleven acres to be used as the Margaret Townsend Girl Scout Camp, where it was used until the Girl Scouts relocated to Camp Tanasi in 1959, a much larger location (419 acres) on Lake Norris. The Job Corps was there for only four years (1965-1969). In 1969, Maryville College in coordination with the National Park Service operated an environmental education center at Tremont until 1979. The center closed for repairs, but was reopened by the Great Smoky Mountains Natural History Association. In 1986, the name changed to Great Smoky Mountains Institute. (For more information, see this excellent timeline)

Although the Job Corps program counts for a very brief period of Tremont’s history, it was still a pretty important chapter. The Job Corps opened in December 1965, nearly a year after Catoctin Mountain Park, the very first center, began operation. Job Corps administrators wanted to open the center early in the summer of 1965, but standards for the Job Corps facilities changed, which delayed the construction of centers at Tremont and Oconaluftee. Tremont was a 100-man center, and what makes it different from other centers that I have studied, is that it was predominately African American. It could provide interesting information about the experience of African Americans in the NPS during the Civil Rights Movement. The Tremont Job Corps Center closed in 1969 when President Nixon reduced the program, closing nearly sixty conservation centers including all but three of the NPS Job Corps Centers.

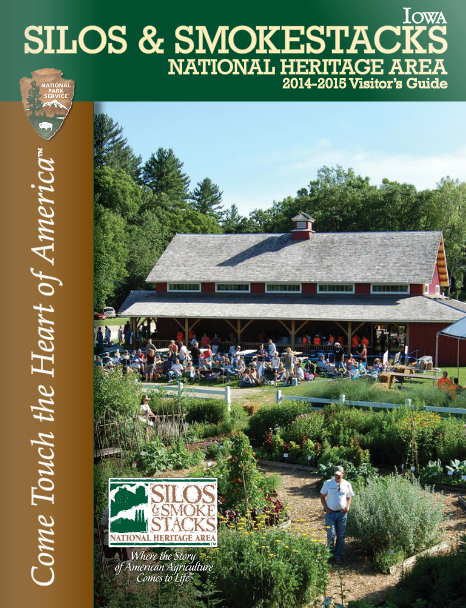

Map of Tremont Campus, circa 1965-1966. Source: National Archives.

The Tremont campus has undergone many changes over the years, but the Job Corps legacy is still readily visible on the landscape. There are still four buildings from that period that remain and a number of important landscape features. Additionally, the circulation pattern remains the same. Unfortunately, the dormitories, dining hall, administrative building, and staff trailers are no longer extant. Despite the brevity of the Job Corps program, I wonder if the GSMI would even exist if the Job Corps had not built a campus at Tremont.

Work Building

The work building was part of the original center that opened in December 1965. It would have been one of the first buildings that corpsmen saw when they arrived at the center, reminding them of the reason why they were there: conservation work. Tremont corpsmen completed trailwork, roadwork, landscaping, and rehabilitated the campground at Cades Cove. Today, the Work Building is now used as the administrative offices and gift shop for GSMI.

Work Building, now administrative offices for GSMI.

Gymnasium

The gymnasium was one of the most important buildings for Job Corps centers. Corpsmen arrived at Catoctin Mountain Park in January of 1965, and staff quickly realized they didn’t have a place for these young men to recreate during winter months. These gymnasiums were essential for morale. Contractors and corpsmen constructed the gymnasium at Tremont in 1966. In 1984, the gymnasium was converted to a new dining hall and classrooms. However, the parquet floors remain and if you go up into the attic, you can still see the upper reaches of the gymnasium.

Vocational Building

Corpsmen also helped contractors build the vocational building in 1966. Here, they would learn skills such as small engine repair or welding to better prepare them for a post-World War II economy. In the 1980s, the vocational building was converted into a dormitory.

Side elevation of Vocational Building, now a dormitory.

Pavilion

This is why visiting these places on the ground is so important. This structure wasn’t on my radar until GSMI staff mentioned that they believed it dated from the Job Corps period. What is interesting about this structure is that it has an extraordinary amount of welding work. When reading through my files, I saw recommendations from staff that welding would be a good vocational program for this center. Job corpsmen may have built this structure for practice.

Pavilion with Gymnasium in background.

Paved Surface Area and Playfield

These landscape features were part of the original 1965 campus. Administrators held the center’s opening ceremony on the paved surface area in April 1966. It is also a physical reminder that corpsmen were between 16 and 21 years old and recreation was an important part of the program. Adjacent to the paved surface area is the playfield, which is still used for this purpose. According to GSMI staff, the campus used to be much more open, but they have started planting native trees and grasses to reduce mowing. Fortunately, this area remains an open space.

Surfaced Play Area with Playfield behind vehicles.

Bridge

Another important landscape feature is the bridge at the entrance of the center that goes over the Middle Prong of the Little River. One of the first graduates of the Tremont Job Corps was an African American man named Frank Carruthers. He left the Job Corps to join the Marine Corps. There is a picture showing corpsmen lined up along the bridge “drumming” him out of the Job Corps. Corpsmen may not have done this for every graduate, but it is a pertinent reminder that some joined the Armed Forces during the Vietnam War.

Material Culture

For those historians interested in material culture, another interesting find during my September visit were wooden benches in the dining hall. GSMI staff had pictures of the benches from 1970, which points to the theory that they were constructed by corpsmen. Catoctin had a sign making center and constructed picnic tables for parks in the National Capital Region. It is completely plausible to me that corpsmen built these benches during the winter months to learn basic woodworking and construction skills.

Benches believed to have been constructed by Tremont corpsmen. Parquet floors also original to Gymnasium.

Unfortunately, the archival records I found at the National Archives and park only cover the years 1965 to 1967. I would need to do more research to find out about Tremont corpsmen activities between 1968 and 1969. Most NPS Job Corps Centers had at least one major multi-year project for corpsmen, but so far, I haven’t found such a project for Tremont. It could be that since GRSM is such a large park, regular maintenance was enough to keep the 100-man center busy.

I’d like to mention one new source of information that I found very valuable while doing this research. The Open Parks Network launched right around the time as I was researching Tremont. I found a whole trove of historic photographs from the convenience of my own office, which was extremely helpful to me. I’m very excited to have this resource for future projects. Did I mention it is free? FREE!